December in Paris gave us the opportunity to reflect on the cultural differences between the U.S. and France--since we were able to take a quick trip back home. Ny parents also came to visit for a second time, and we enjoyed the holiday festivities together.

For photos, click here.

Kimberly

After having spent almost three months in France, we had the opportunity to make a quick trip back to the States. The company I am going to work for next year, Bain & Co., was having a weekend meeting for all the “offerees” in next year’s class…and they offered to fly me and Dan back to San Francisco for it. Needless to say, we jumped on the opportunity to visit family and friends, and even worked in a stopover in Chicago.

What surprised me most about the trip, though, were the little things that I was completely in awe of, the little things we take for granted in the U.S., the little things I did not even realize I had missed.

I found myself way too excited and content to be in a Walgreens. Mind you, one that I had never set foot in before in San Francisco. Wandering around the aisles, I realized that I could easily find anything I needed. This concept of logical organization and standardization between stores is a completely foreign concept in France—and something so common we don’t even notice in the U.S. And, if I couldn’t find what I was looking for, a friendly Walgreens employee would be happy to help. Try that in a store in Paris, you will be lucky if you can find anyone…and if you do, you’ll most likely just get a shrug of the shoulders and puff of the lips as your response.

But at the end of the long weekend, I found myself quite happy to be returning to Paris, with its inefficiencies and indifference—but also with its

joie de vivre, slow pace of life, and incomparable cheese.

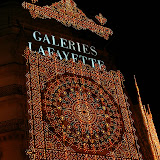

After we returned, we had to prepare for my parents’ second visit to our new home. While they were here, we visited all the parts of the city that had been illuminated and decorated for the holiday season. We saw a special projection show at Notre Dame, a concert at Eglise Trinité, the lights on the Champs Elysées, and the amazing displays at Galaries Lafayette and Printemps. We were leaving together in a few days for our Christmas/New Year’s trip to Jordan and Egypt. So we prepared by attending an amazing exhibition at the Grand Palais of the underwater archaeological expedition the French carried out in the Mediterranean Sea just north of Alexandria. It certainly whet our appetite!

As we continued the uphill battle of dealing with French Bureaucracy, we had plenty of opportunities to observe the differences between the American and French attitudes towards working. (At this point in the paperwork saga, someone had apparently lost both of our

Autorisations du Travail (work permits), and now we were jumping through an innumerable amount of hoops to try to get at least a copy of them.)

So when our internet stopped working, I was horrified when the nice man at France Telecom told me that I had no choice but to call Customer Service to have them resolve the issue. If you think you speak another language, it really is another test altogether when you are trying to explain an internet problem and understand instructions from a tech support guy over the phone. I now know that

debrancher means to unplug. And

clignotait means blinking (which the light on our internet box was not). After several times of

debrancher and

brancher and checking for

la lumière clignotait, the tech support man told me that I had to make a

rendez-vous for someone to come to our apartment to see exactly what the problem was.

Random aside: in the U.S. we have this incredible skill of romanticizing everyday French words and phrases. In the U.S. a

soirée is a fun night out, usually involving doing something swanky. In France, it just means evening. My favorite one by far is

rendez-vous. Literally, it translates as “return yourself”. In the U.S. we have decided it means a special, romantic meeting, often somewhat illicit—and definitely something that you would eagerly anticipate. In France, it just means appointment, often something painful and bureaucratic—and usually just some additional step in the bureaucratic nightmare that you are dreading.

So when the date of our

rendez-vous finally came, I was not looking forward to waiting around all day for a grumpy French cable guy to show up and tell me that he could not solve our problem, shrug his shoulders, and leave. Boy was I surprised when he arrived on time and with a smile on his face. He proceeded to quickly ascertain that France Telecom had signed us up for an Internet connection that was too fast and too much data for our old phone-line to handle. And while he was solving our problem, he started to ask me what the differences were between the U.S. and France. What did I miss from home?

Having just returned from the U.S., I knew what my answer was to that question: customer service. I explained that in the U.S., it was unthinkable for the supermarket to close fifteen minutes early because the manager just felt like going home. That when you walk into a store, people come over to help you—rather than ignore your presence entirely. The fact that you have to pay extra to call customer service numbers is even more proof of the difference. In the U.S., you call a 1-800 number for customer service, meaning that it is completely free, not even the price of a local call. In France, it is also an 800 number, but that means the opposite: like a 900 number back home, it means you pay extra, sometimes several Euros a minute, to talk with someone to resolve a problem that you don’t want to have anyway. The cable-guy agreed this seemed like a funny approach, and even commented that it might create the incentive for French companies to make more problems so they could make money through their customer service hotline!

He asked me why I thought the difference was so strong. It’s a complicated answer, of course. The cultural differences cannot be denied, for sure. And there is the notion that America is “the land of opportunity” where anyone can work hard and become a millionaire—whereas France’s rigid class system still reeks of nobility. But I explained that I think a lot of it has to do with incentives.

In France, the employment laws are so strict, that you cannot terminate an employee without jumping through numerous hoops and paying a very pricey severance package. And that is if you can fire him at all—often you simply cannot. In the U.S., if you aren’t doing a good job, you could show up tomorrow and find out you have been let go. And in many jobs, your pay is a function of how well you do—especially in sales or retail where things are commission based. The French choose a career, usually at the age of sixteen when they select their specialty for the baccalaureat, they get certified for the career, and once they start in it, they rarely change. Why change when your employment is essentially guaranteed? And if you don’t inherently love your work, why try?

Before I continue with the French bashing, let me say that there is something truly refreshing about the lack of commercialism over here. Yes, often you meet employees who could care less if you wanted to buy something. Yes, I agree that most French people would not even understand the statement “The customer is always right.” But you also often meet employees who chose this job or opened this store because they truly love their work and helping customers. What you NEVER meet are employees who are trying to upsell you into a product you don’t need because their livelihood depends all on commission. So, if you can’t get help in this France Telecom office, try going to another. Surely after several visits, you will eventually find one of the smiling representatives who when you gush, “Thank you so much. You have been the most helpful person throughout this entire process.” They respond incredulously, “

Mais bien-sûr! Cést mon métier!” (“But of course, it’s my job!”)

After an extra half-hour of chit chat and dissection of our cultures, politics, and economic systems, the cable-guy left and wished me a

bon journée (good day). It wasn’t until a few weeks later that I found the following passage in Adam Gopnick’s “Paris to the Moon” that so perfectly sums up the differences in attitude that we had been trying to articulate.

"The Eiffel Tower incident of the summer of ’97 illustrates a temperamental and even intellectual difference between the two cultures. Most Americans draw their identities from the things they buy, while the French draw theirs from the jobs they do. What we think of as “French rudeness,” and what they think of as “American arrogance,” arise from this difference…. For us, an elevator operator is only a tourist’s way of getting to the top of the Eiffel Tower. For the French, a tourist is only an elevator operator’s opportunity to practice his

métier [profession] in a suitably impressive setting.

The French ideal of a world in which everyone has a

métier but no customers to trouble him is more practical than it might seem. It has been achieved, for instance, by the diplomats inside the quai d’Orsay, who create foreign policy of enormous subtlety and refinement which has absolutely no effect on anyone outside the building….

The elevator operator dreams of going to the top of the tower alone in his elevator, while the Anglo-Saxon tourist, in her heart of hearts (and he knows this; it’s what terrifies him the most), dreams of an automatic elevator. When the two ideals—of absolute professionalism unfettered by customers and of absolute tourism unaffected by locals—collide, trouble happens, pain is caused. Americans long for a closed society in which everything can be bought, where laborers are either hidden away or dressed up as nonhumans, as not to be disconcerting. This place is called Disney World. The French dream of a place where everyone can practice his

métier in self-enclosed perfection, with the people to be served only on sufferance, as extras, to be knocked down the moment they act up. This place, come to think of it, is called Paris in July.

More favorite restaurants:

Le Comptoir du Relais

9 Carrefour de l'Odéon - 75006, Paris - 01 44 27 07 97

(One of the hottest places in Paris these days, run by the guy who really started this movement towards high quality "bistro food"...Senderens and Robuchon have since decided this is a good idea, blowing off Michelin and "downgrading" their fancy restaurants. The food is amazing-and very afforable for the quality of cuisine. Book a table a month in advance for dinner during the week (the 40 prix fixe is supposed to be amazing) or take your chances on the weekend...or come for lunch, like we did!)

La Bastide Odeon

http://www.bastide-odeon.com/7 rue Corneille - 75006, Paris - 01 43 26 03 65

(A great taste of Provence in the heart of Paris. The food was of exceptional quality and presentation. A refreshing meal out different from your typical Paris Bistro.)

The following three places are great for some sweet snacks during your stay:

Ladurée

http://www.laduree.fr16 rue Royale - 75008, Paris - 01 42 60 21 79

75 avenue des Champs Elysées - 75008 Paris - 01.40.75.08.75

21 rue Bonaparte - 75006 Paris - 01.44.07.64.87

(World famous macaroons..and no, not like the Jewish cookie. Imagine a chewy French meringue with tasty fillings like chocolate, coffee, raspberry, or vanilla)

Gérard Mulot

http://www.gerard-mulot.com/76 Rue du Seine - 75006, Paris - 01 43 26 85 77

93 Rue de la Glacière - 75013, Paris - 01 45 81 39 09

(One of the best boulangeries and patiserries in Paris. Come here for the makings of an exquisite picnic in the Luxembourg Gardens. Also have salads, sandwiches, quiches, and other prepared dishes.)

Angelina

226 rue de Rivoli - 75001, Paris - 01-42-60-82-00

(The place in Paris for hot cholocate...no, not Swiss Miss style, more like a melted bar of chocolate in a cup!)